Disney Research just published a paper about bringing Olaf (yes, the talking snowman from Frozen) to life as a physical walking robot. Before you roll your eyes at another “AI-powered entertainment demo,” this is actually interesting engineering work that solves real problems most roboticists ignore.

The Problem Nobody Talks About

Here’s the thing about legged robotics: we’ve gotten pretty good at making robots that can hike mountains, do backflips, and recover from being kicked. Boston Dynamics proved that a decade ago. But we’re still terrible at making robots that look and move like characters people actually care about.

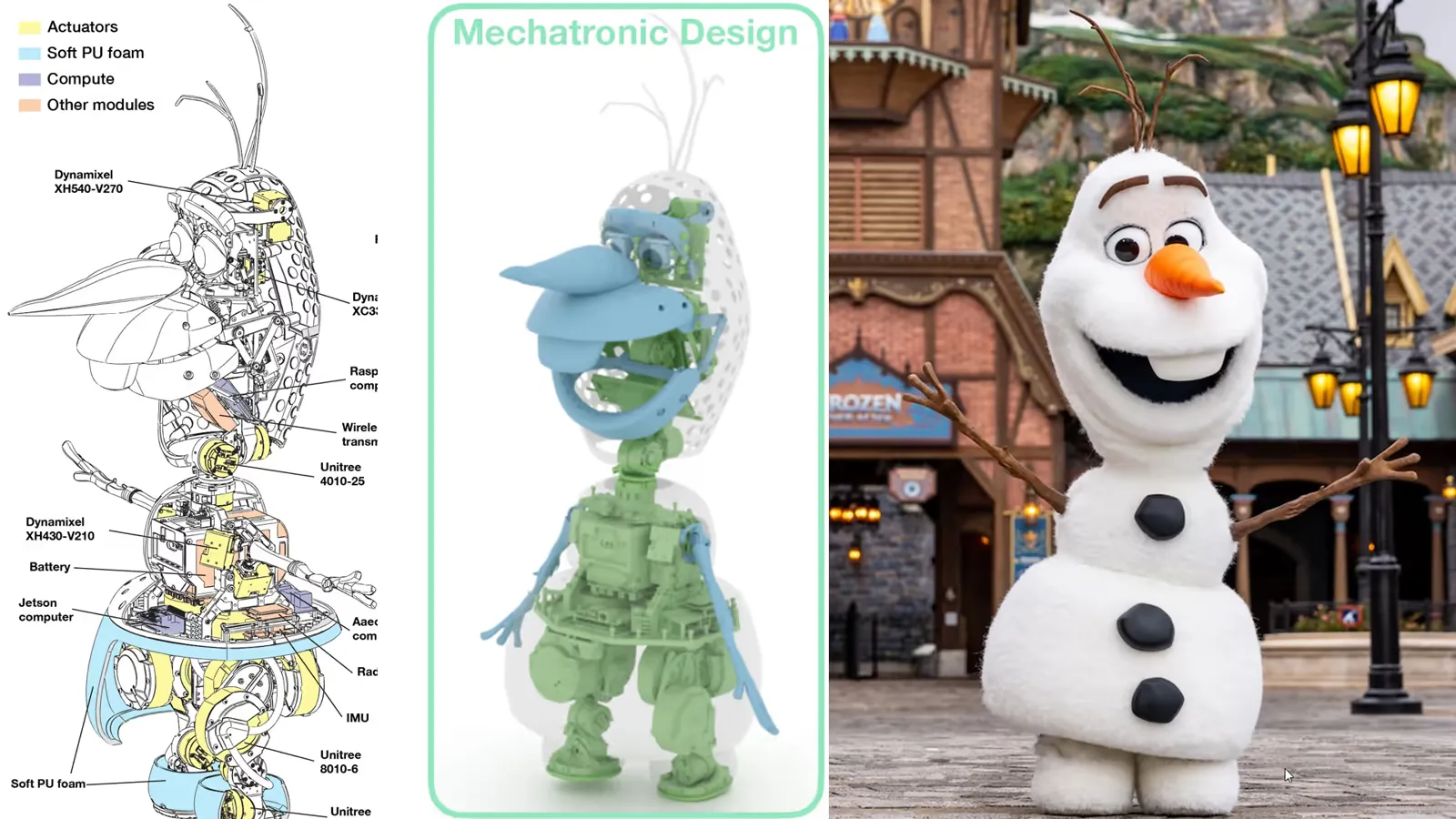

Olaf isn’t built like Atlas or Spot. He has:

- A massive head (relative to body size)

- Tiny snowball feet with no visible legs

- A slim neck that somehow needs to support said massive head

- Arms that float on his sides with no shoulder structure

- A movement style that’s deliberately non-physical and cartoony

Try to map that onto a traditional bipedal robot design. You can’t. The proportions are wrong, the workspace is impossible, and the aesthetic constraints mean you can’t just bolt actuators wherever they fit.

The Mechanical Weirdness

The Disney team’s solution involves some genuinely clever mechanical design that I haven’t seen before.

Asymmetric Legs Hidden Under a Skirt

Olaf’s legs are completely hidden inside his lower snowball body. But here’s the trick: they made the two legs asymmetric.

- Left leg: rear-facing hip roll, forward knee

- Right leg: forward hip roll, rear-facing knee

Why? Because symmetric legs would collide with each other inside the tight volume. By inverting one leg, they maximize the workspace while keeping everything hidden under a soft foam “skirt” that deflects when the robot takes recovery steps.

This also means both legs use identical parts, just mirrored orientation. Fewer unique components to manufacture and maintain.

Spherical Linkages for the Shoulders

There’s no room to put actuators at Olaf’s shoulders (he doesn’t really have shoulders). So they placed the actuators in his torso and drove the arms remotely using spherical 5-bar linkages.

I had to look this up. It’s basically a mechanical coupling that converts rotary motion from actuators buried in the body into the 2-DoF arm movement you see on the outside. Same principle is used in the jaw (4-bar linkage) and eyes (another 4-bar setup for pitch and eyelids).

Remote actuation through linkages isn’t new, but doing it this cleanly on a costumed character is non-trivial. You’re fighting fabric tension, wrinkling, and the fact that the costume obscures all the mechanism geometry.

The Control Problem: When Your Robot Can Overheat

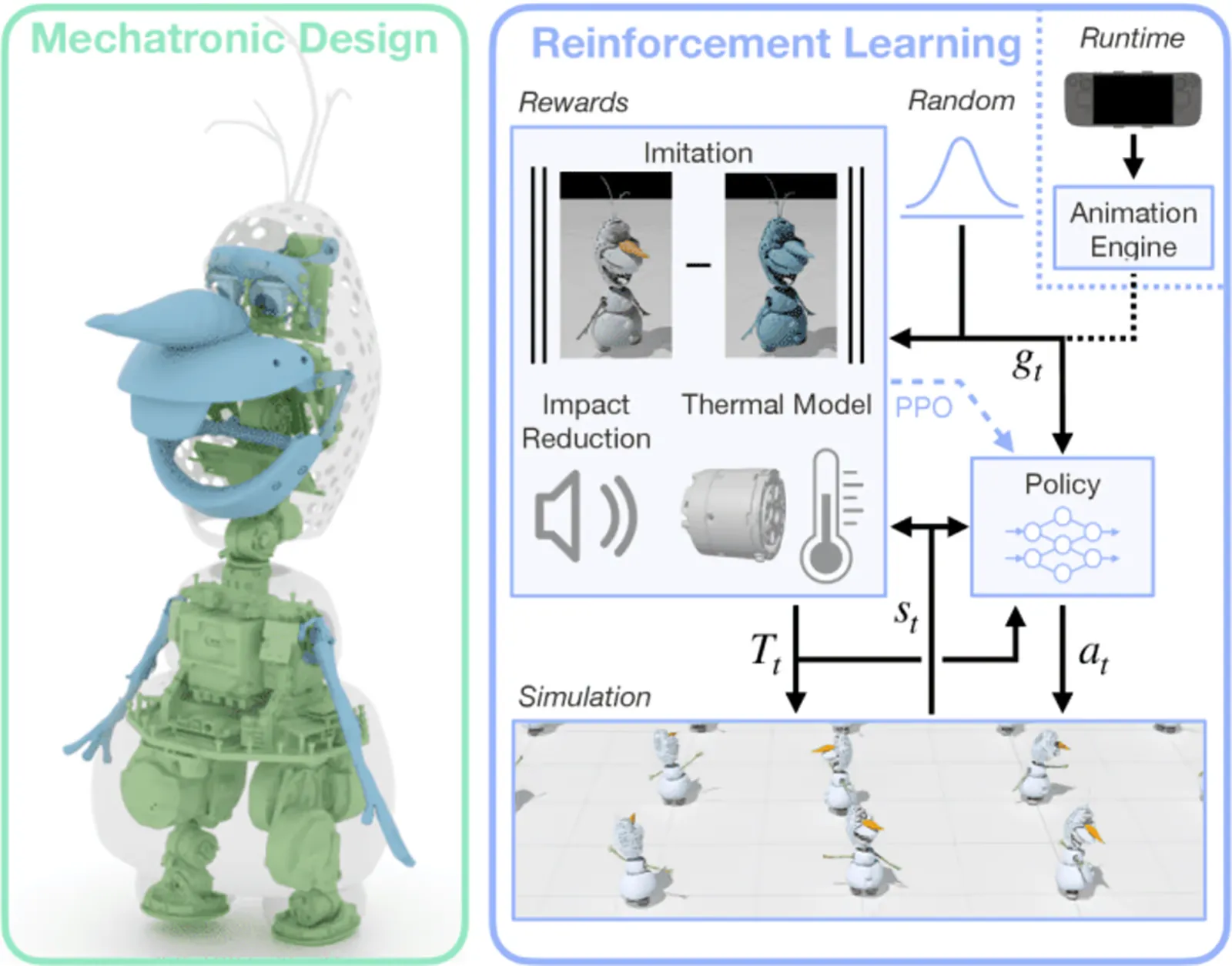

This is where it gets interesting from a machine learning perspective. They’re using Reinforcement Learning with imitation rewards. Train a policy to track animation references while maintaining balance. Standard stuff if you’ve read any DeepMimic-style papers.

But Olaf has a problem traditional robots don’t face: his neck actuators overheat.

“Why?” you ask. Well, that’s because:

- The head is heavy

- The neck is slim (for aesthetic reasons)

- Small actuators = less thermal capacity

- The costume traps heat

Early experiments had actuators hitting 100°C in 40 seconds during certain head motions. That’s not a software bug. That’s thermodynamics telling you your design is fighting physics.

Thermal-Aware Policies (Actually Useful)

Most reinforcement learning papers ignore actuator temperature entirely. The Disney team modeled it explicitly:

Temperature change is driven by Joule heating (proportional to torque squared) and cooled by ambient dissipation. They fit and from real hardware data: 20 minutes of recording actuator temps and torques, then least-squares regression.

Then they added temperature as an input to the policy and introduced a Control Barrier Function (CBF) reward that penalizes the policy when it’s heading toward thermal limits:

Translation: if you’re near the temperature limit, the derivative of temperature better be negative or zero. The policy learns to proactively reduce torque before hitting critical temps.

In practice, this means Olaf will slightly relax head tracking when he’s been looking up for too long, subtly tilting back toward horizontal to reduce sustained torque. The tracking error only increases by a few degrees, but temperature rise slows dramatically. He doesn’t overheat, and most people won’t notice the tracking adjustment.

This is not a hack. This is proper constraint-aware control that should be standard in more robots.

The Noise Problem

Here’s a detail most robotics demos skip: footstep sounds matter when you’re trying to sell the illusion of a living character.

Heavy robotic footfalls ruin believability. Olaf’s supposed to be a light, bouncy snowman, not a 15kg machine stomping around.

They added an impact reduction reward that penalizes large velocity changes in the vertical direction during foot contact:

The cap prevents the reward from exploding during simulation contact resolution (physics engines can generate huge velocity spikes that would destabilize critic learning).

Result: 13.5 dB reduction in mean sound level over a 5-minute walk. You can hear it in the video. The before/after is obvious. The policy learns to place feet more gently without destroying tracking accuracy.

The Heel-Toe Gait Detail

One more thing: Olaf’s walk cycle uses heel-toe motion. Most bipedal robots don’t bother with this because flat-footed contact is more stable. But heel-toe is what makes human (and Olaf’s) walking look natural.

They trained a policy without heel-toe motion as an ablation. Quote from the paper: “the resulting motion appears more robotic.” You can see it in the supplementary video. It’s subtle but it matters.

This is the kind of detail that separates “working robot” from “believable character.” And it’s extra credit because heel-toe contact increases control complexity and makes balance harder.

Implementation Details That Matter

Training:

- PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) in Isaac Sim

- 8192 parallel environments on a single RTX 4090

- 100k iterations (~2 days of training)

- Policies run at 50 Hz on-robot, upsampled to 600 Hz for actuators

The policy is conditioned on high-level control inputs (neck targets, path velocity, etc.) that come from an Animation Engine. This engine:

- Plays looped idle animations (eye saccades, subtle arm shifts)

- Triggers short animation clips (gestures, dialogue)

- Maps joystick inputs to real-time control during puppeteering

Runtime architecture is borrowed from a previous Disney Research paper on bipedal character control. They’re iterating on a proven system rather than reinventing everything.

Why This Matters Beyond Entertainment

I’m not pitching this as “the future of robotics.” It’s a research project for theme parks and entertainment. But the techniques are transferable.

Thermal-Aware Control

Any robot with high torque-to-size ratios (humanoids, manipulation arms in tight spaces) will face thermal limits. Explicitly modeling temperature and adding it to your policy is better than hitting current limits and hoping for the best.

Acoustic Objectives

Service robots in homes, hospitals, warehouses (anywhere humans are present) need to be quiet. Reward shaping for impact reduction is cheap to implement and works.

Asymmetric Designs

We’re too married to symmetric leg configurations because biology does it that way. But if you’re working in constrained volumes (exoskeletons, compact platforms), asymmetric kinematics might give you the workspace you need.

Remote Actuation Through Linkages

When you can’t put actuators at joints (space, weight distribution, aesthetics), well-designed linkages let you place them where you have room. The engineering is harder but the tradeoffs can be worth it.

The Brutal Honesty Section™

This robot is not robust. It’s not going to hike trails or handle adversarial perturbations. The design is optimized for controlled environments (theme parks, stages) where the floor is flat and nobody’s trying to kick it over.

The asymmetric leg design trades workspace for complexity. You’ve got two different leg orientations, which means more failure modes and harder maintenance.

The thermal model is first-order and ignores mechanical friction and enclosure heating over long durations. It works for short demos but probably doesn’t scale to 8-hour shifts without breaks.

And the impact reduction reward helps but doesn’t eliminate noise. Just makes it less obnoxious.

What They Got Right

Despite those limitations, this is good engineering because:

-

They shipped. This robot walks in the real world. It’s not a sim-only result.

-

They respected constraints. Instead of fighting the character design, they embraced it and solved around it.

-

They measured what mattered. Temperature, noise, tracking error. All quantified and improved.

-

They open-sourced the approach. The paper has enough detail to replicate the methods (thermal CBF, impact rewards, asymmetric leg design).

-

They avoided hype. The paper doesn’t claim this solves AGI or general-purpose robotics. It solves the problem of making Olaf walk smoothly without overheating or sounding like a jackhammer.

Final Thoughts

Legged robotics has spent decades chasing functional performance: speed, efficiency, robustness. That’s led to impressive machines, but most of them look and move like… machines.

Disney’s Olaf project flips the priority: character fidelity first, function second. And in doing so, they ran into problems (thermal limits, acoustic quality, tight workspaces) that forced novel solutions.

Is this the future? No. But it’s a reminder that different objectives reveal different problems, and solving those problems generates techniques the rest of us can steal.

Plus, it’s a walking snowman that doesn’t melt. That’s just cool.

Paper (arXiv): Olaf: Bringing an Animated Character to Life in the Physical World